I’m back! Well, sort of. Like Michael, I have a little more time around the holidays to write, so I’ll been getting my pen out and cranking out some posts. It’s also a welcome distraction from all the news that routinely induces aneurysms, although I don’t have much choice but to keep on keepin’ on and fighting the good fight.

Over this year, my involvement in travel hacking transitioned from raw churning (credit card sign-ups to receive the bonuses) to generating large stashes of miles and points by manufactured spending (buying cash equivalents like gift cards and selling them or otherwise converting them to cash). This was rooted largely in pragmatism. Going into this year, I had exhausted a lot of the low-hanging fruit in terms of credit card signups, and moreover, banks weren’t taking too kindly to all my new accounts and credit inquiries (I wouldn’t if I were them, either).

Moreover, I had a few friends who taught me that, if you nail down the processes, earning points via MS is significantly more efficient than sign-ups. You can earn the currencies you want or need in pretty much arbitrary volume, and indeed, as I do my tallies this year, I earned more miles across every major currency that I had in either of the past two years.

One of the most interesting developments for me, given how much I emphasize opportunity cost when chasing deals, is that once you reach a certain scale, opportunity cost is irrelevant. If you’re constantly pushing your total available credit, there is no opportunity cost to earning a normally sub-optimal currency (say, Club Carlson or Virgin America points), since the alternative to putting your marginal spending on a card is not having the spending at all. At that point, all you need to balance is the real cost per mile versus the rewards, and if it’s worth it, going ahead.

It’s clear therefore that real cost is a factor in determining if/how to pursue MS, but is it the only one? I’d like to argue that there are two others: spending density and float time.

Table of Contents

Spending density

Before you wonder why you’ve never heard of this term before — it’s completely made up. However, you can probably intuit the meaning from the name. Roughly, I think of the “density” of my spend as the points return per dollar of spending generated. All else equal, an MS method with higher spending density is preferable to one with lower spending density.

How is this different than saying “earning 2x is better than earning 1x?” Take the following example: let’s say you have one method that has a real cost of $10 per $1000 of spending and earns 2x, and compare it to a method that has a real cost of $5 per $1000 spend, but only earns 1x. The same $10 will get you the same number of miles in both cases — 2000 miles per $10, for a real cost per mile of 0.5 cents, but the first method will only require you to spend $1000 whereas the second will require $2000 in spending. Therefore, we would say that the ‘density’ of the first method is 2/$ whereas the second method is 1/$.

What happens if we let real cost vary? We can’t compare options directly anymore, since it’s not objectively better to trade density for cost and vice-versa. The trade-off depends on your own values. Let’s take another example, where one method costs $10/$1000 while earning 2x, while another method costs only $1/1000 but earns 0.5x. In the long-run, you’ll come out ahead with the latter method, but considering that your credit limit (not to mention time) is constrained, it might not be the best option for you. In order to earn the same 2000 points as the first method, you’d have to spend 4000 dollars.

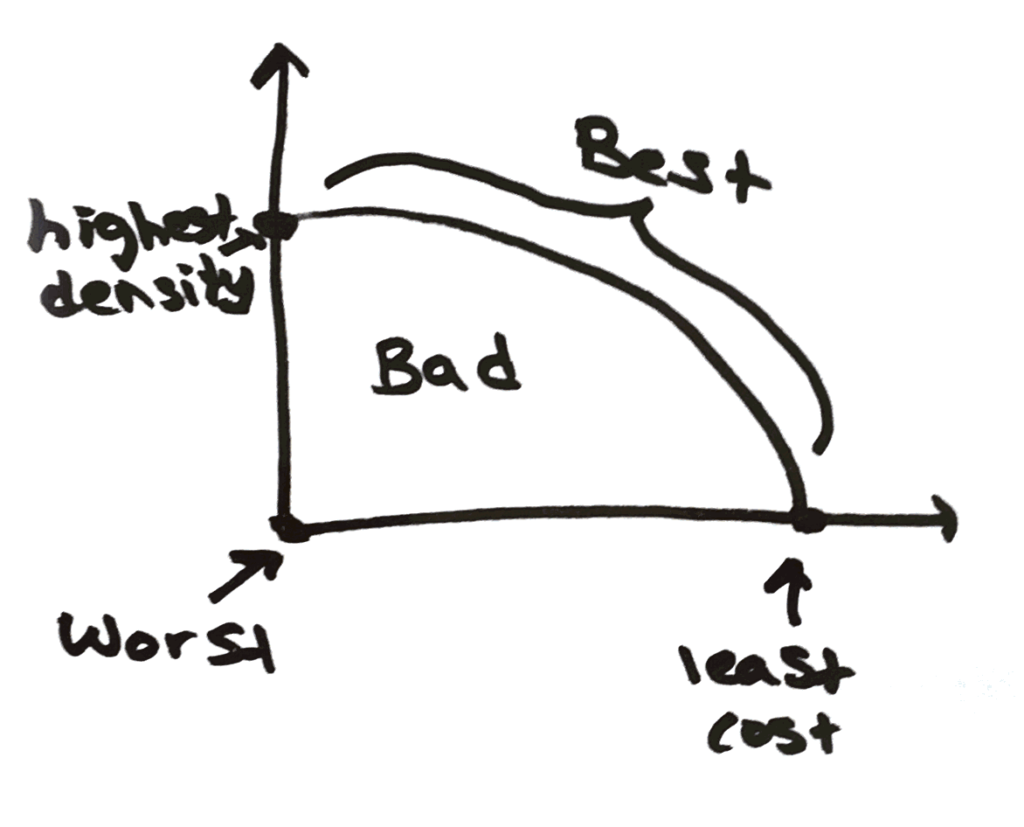

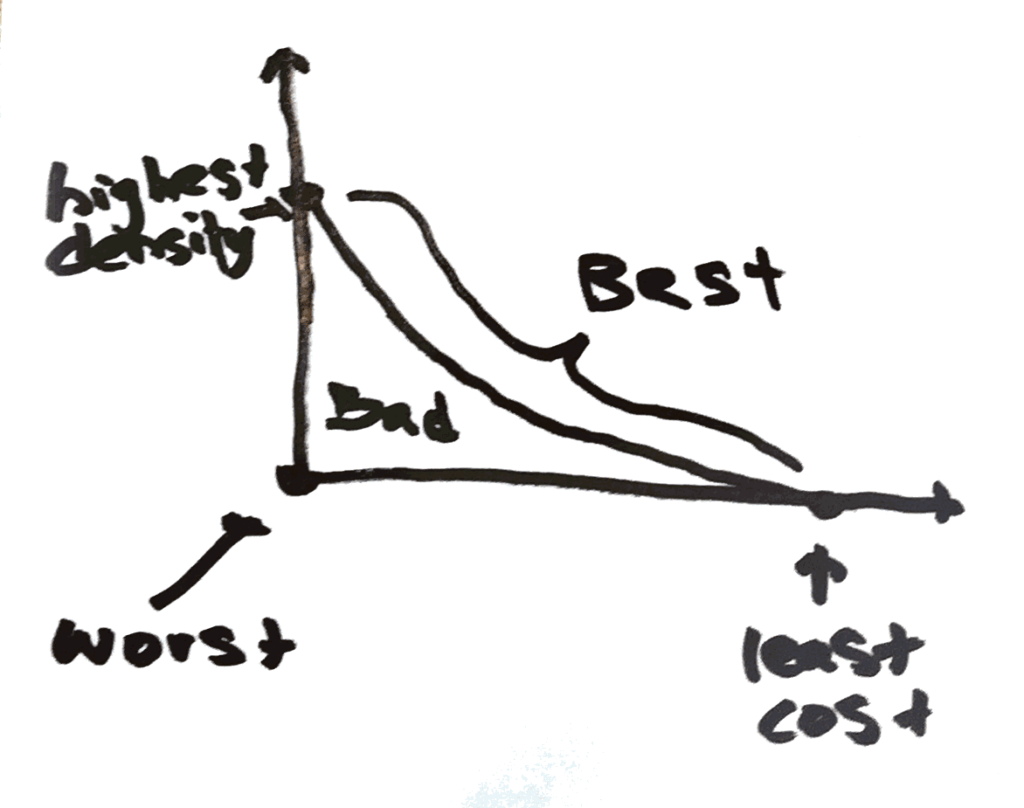

For me, the cost trade-off here is significant enough that I would probably opt for the slower-earning, but cheaper method, in particular because I don’t burn miles all that quickly. However, someone who needs to fly a family of four might opt for the former, since they earn miles four times as ‘fast.’ That difference trade-off might manifest itself as the following graphs (for the mathematically inclined, the convexity of the curves capture the difference in valuations; also, technically these are indifference curves, so saying the curve represents the ‘best’ choices isn’t entirely accurate):

A person earning for a family might trade a lot of cost for even a little bit of density.

Whereas in absence of the density concept, we’d have the same graph:

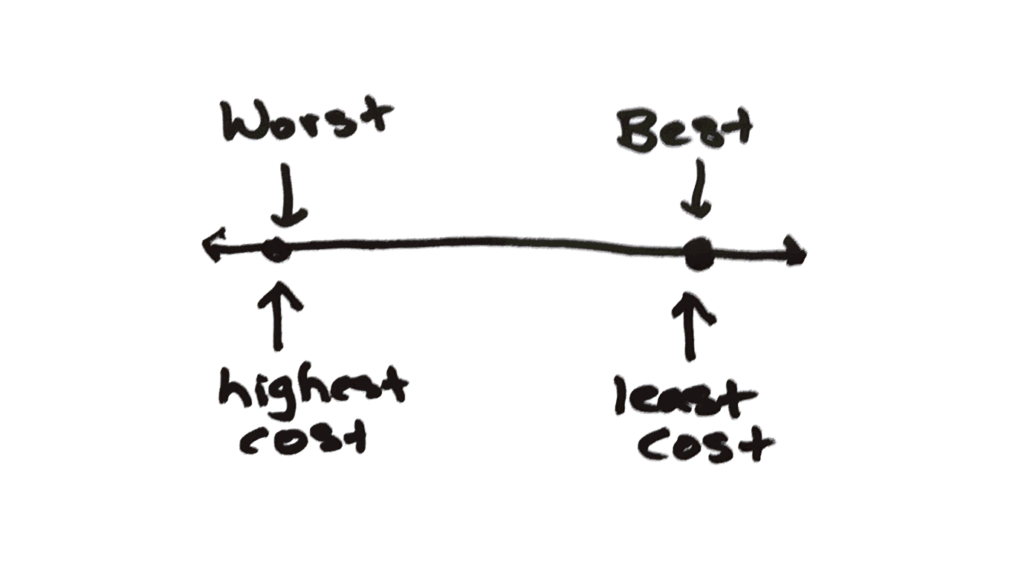

Put simply, spending density is a metric that tells you how to allocate your spending among simultaneous options, assuming that real costs are the same or negligibly different.

Float time

However, your credit limit is the most amount of debt a bank is willing to extend to you at a given time. Once you pay off your balance (usually), you can start spending again. (Doing this multiple times in the same statement is known as ‘cycling,’ which you should avoid since banks are not particularly fond of it). Therefore, the length of time it takes for you to recoup your money (also known as ‘float’) will affect your overall ability to earn miles.

Back to examples. Say we have two options, both of which have the same real cost per mile and spending density — 0.5 cents per point and 1 point/$, respectively. However, one of the options only takes one month to get your money back and the other takes two months. It’s pretty obvious which option you should prefer. The former will, for the same real cost per mile, allow you to earn twice your credit limit’s worth of miles as the second option in the same amount of time.

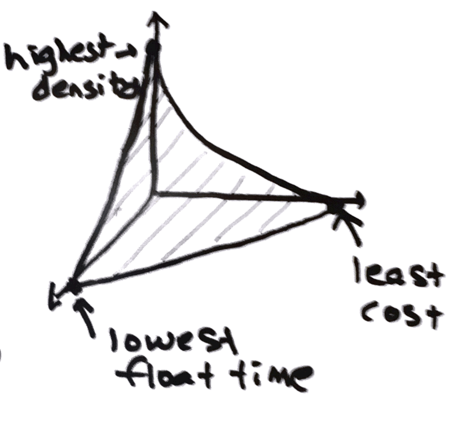

As with the above, we can draw a new graph, this one in 3-D:

If you’ve been paying attention, you’ll notice that both of float time and spending density are measures of opportunity cost (which, in fairness, you should have expected in a post from me), except with different constraints.

Conclusion

My journey through travel hacking and miles-earning has followed a common progression: first I focused on churning, then I focused on opportunistic spending, and then I moved to manufacturing spend. The progression through each stage reflected a shift in the assumptions I made about the world. I started under the assumption that spending is extremely constrained, which made churning the best way of earning miles. Then, I realized that there were ways to increase my spending some amount that was less than the credit I had access to, which dictated my focus on opportunity cost as the way of evaluating things. Then finally, my ability to generate spending became large enough that I threw opportunity cost out the window, since the only limited thing was my credit. At that point, real cost began to matter most, but as I’ve discovered over the last few months, that’s not the only thing I’ve been factoring into my decision making. Since I have to allocate my credit over multiple different types of spending opportunities, each with similar real costs, I needed some way of choosing among those opportunities. Spending density and float time give me such a framework.

Happy hacking!

I tend to look at things in $ per hour of my time, or $ per card that I MS. This is because I still have ample credit limit and though I consider float time, I’ve been too busy to reach a point of hitting that barrier either. My limiting factor is how long it takes me to walk the MS circle. If it’s an online circle, then some cards earn 50 cents each and some $2 each. Yet they take a similar amount of time each. Also, for MS going store to store, I unload slowly. It takes me about 30 min to unload 3 cards. If one case has $100 gift cards for me to MS and I’m earning 3%- that’s $3 per card. Or $9 per 3 card unload, earning $18 per hour, minus gas. If another opportunity uses $500 cards but yields only 2% gain, that’s $10 per card, or $30 per 3 card unload, earning $60 per hour, minus gas. Since my time is limited (though at $60 per hour I’m surprised I don’t use this method more…) I try to choose the higher $ per hour methods and let the others fall by the wayside. Explaining this leads me to another important factor in choosing what to MS- some limits are not pissing off the pieces of the deal. Some places don’t do well with large quantities and ban/block those folks that have done such. I like to keep my opportunities open and not burn any bridges. This does mean that when others “go big or go home” and an opportunity dies, that I sure did not get all I could have. But I also avoid being someone that has been banned from Target or giftcards.com or any banks… Guess it’s a trade off. I plan on using my good credit and bank relations for real estate over years in the future so need to keep those things in good condition. Though I sure do regret not having hit some things harder when I could have! The learning curve of the newbie.

Also, your natural progression is interesting to me as I have been stuck avoiding much churning for different reasons since I started, so entered the world of MS and other deals practically from the starting gate of my miles & points pathway.

Yeah this is totally valid. I tend to approach analyses assuming things (personal time in this case) are unlimited, unless I state otherwise. That lets me focus on the point I want to highlight in a vacuum.

In this case, however, time is kind of something we can’t avoid. Also great points about burning bridges/relationships. I’ve encountered a range of opinions on this, although I tend to fall around where you do.

Re: credit and banks. My credit is an asset. This asset gets me lower interest rates on a mortgage or student loan, or it can get me credit card miles. I don’t have plans for the former in the near future, so I use this asset for the latter.

What I really mean to say is, thanks for the thought provoking post! Great variables for analysis, great post!

Thanks :)!

Any suggestions on where a 5+ year travel hacker can find intel on the latest MS angles? Back in the good ol’ days I started with coins from the Mint, then Vanilla reloads at Office Depot, then Visa GCs at Simon->Bluebird, then Nationwide Visa Buxx…and then the trail went cold…

Secondarily, just a nod of appreciation for the economic approach you take to this sport. Thanks for another solid post.

Saverocity L2 forums, Travel Codex forums, FreequentFlyers’s newsletter. And thanks, glad you enjoyed!